Fisheries are the main activity contributing to selective extraction of species in the Baltic Sea. The principal species targeted in the commercial fishery are cod Gadus morhua, herring Clupea harengus, and sprat Sprattus sprattus, which constitute about 95% of the total catch. Other species having local economic importance are salmon Salmo salar, plaice Pleuronectes platessa, dab Limanda limanda, brill Scophthalmus rhombus, turbot Scophthalmus maximus, European flounder Platichthys flesus, Baltic flounder Platichthys solemdali, pikeperch Sander lucioperca, pike Esox lucius, perch Perca fluviatilis, vendace Coregonus albula, whitefish Coregonus clupeaformis, eel Anguilla Anguilla, and sea trout Salmo trutta. The overall fishing effort in the Baltic Sea decreased by approximately 50% from 2004 to 2012 (Figure 6). The ICES fisheries overview for the Baltic contains detailed information on the fisheries. The impact of the EU landing obligation has not yet been evaluated, but is likely to change the effect of fisheries on the ecosystem.

Landings

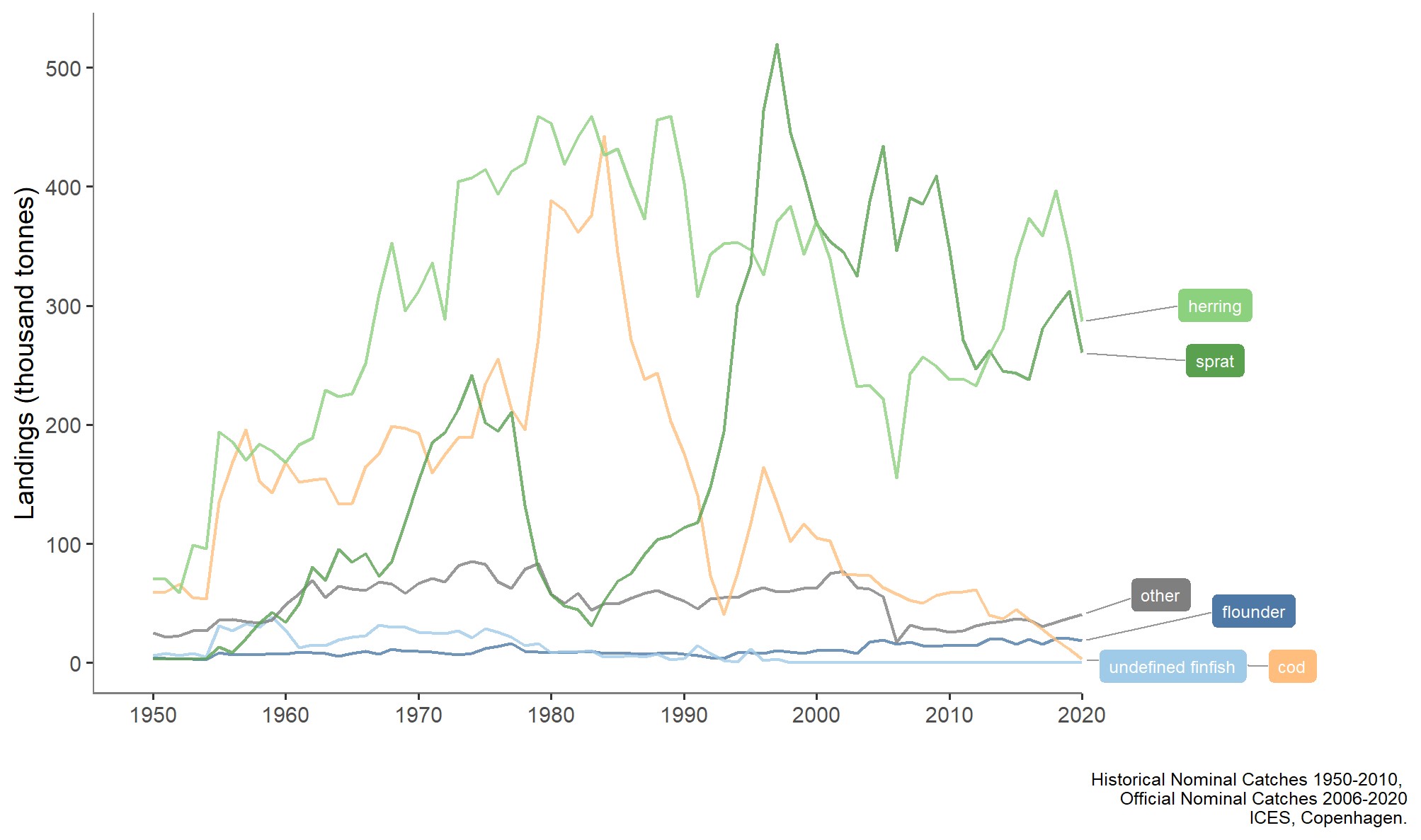

Since the early 1950s, landings of herring and sprat from the pelagic fisheries have dominated the total landings of fish from the Baltic Sea (Figure 7). A decrease in sprat landings in the late 1970s, followed by a decline in cod landings in the late 1980s, led to a marked decline in total landings. Pelagic landings increased in the early and mid-1990s, reflecting an increase in sprat abundance during this period. Since 2003, total Baltic Sea landings have remained fairly stable (Figure 7) despite declining fishing effort. In many areas, recreational catches of coastal species outnumber the commercial catches.

Figure 7: Landings

(thousand tonnes) from the Baltic Sea in 1950–2020, by species. The five

species with the highest landings are displayed separately; the remaining

species are aggregated and labelled as “other”. The “undefined finfish”

category is due to inadequate reporting in early years.

Impacts on commercial stocks

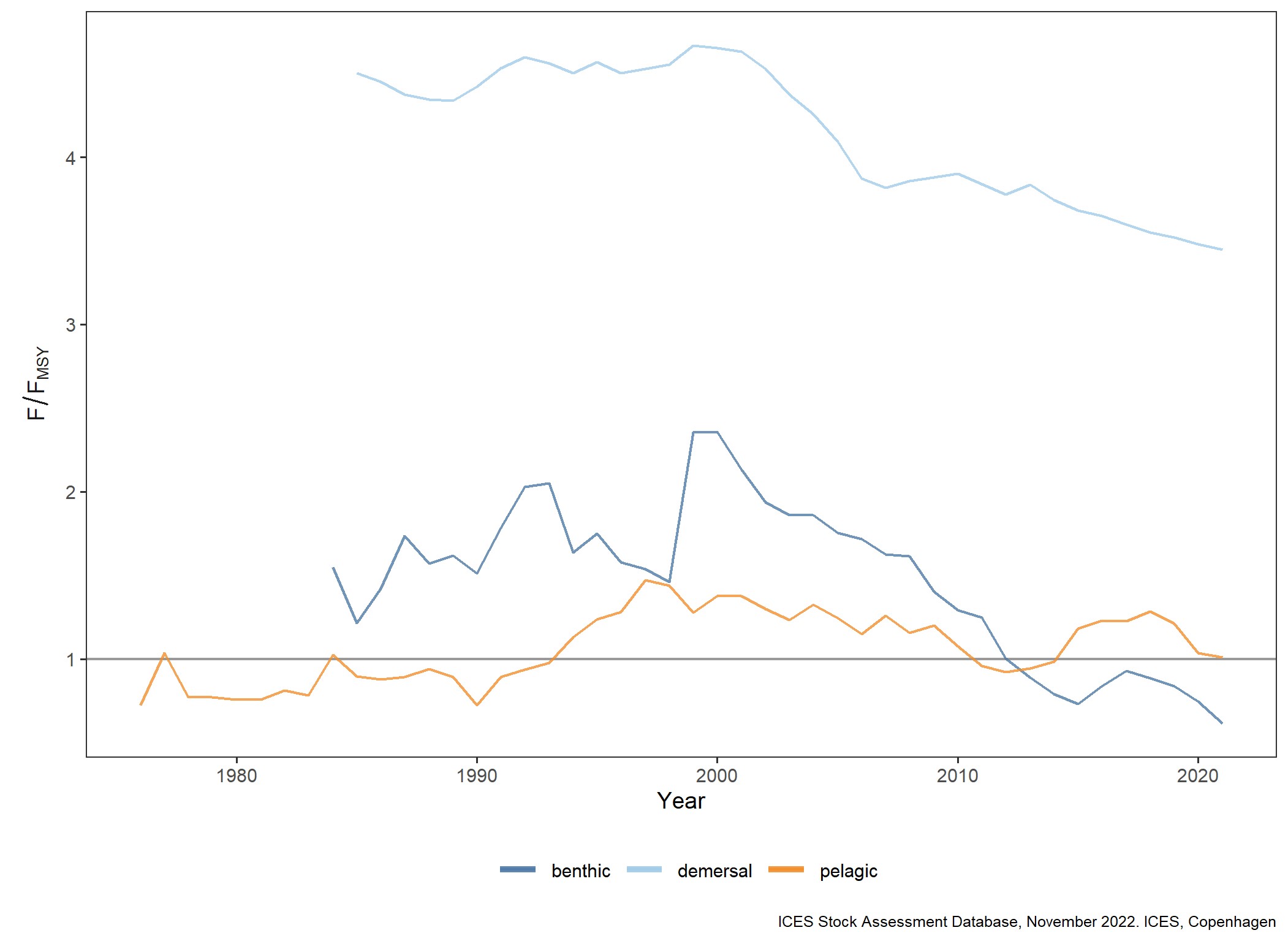

The two major pelagic fish stocks (central Baltic herring and Baltic sprat) are fished above FMSY. The other assessed herring stocks are also fished above FMSY and both stocks are therefore experiencing overfishing, except for Gulf of Riga herring. The mean F for the pelagic fish stocks has decreased in the late 2000s, but has increased in the last few years (Figure 8).

There are two main commercially exploited demersal fish stocks in the Baltic Sea, namely the western Baltic cod and the eastern Baltic cod. The fishing mortality (F) of both cod stocks is above FMSY. It is hypothesized that the reduced mean size and growth of the eastern Baltic cod stock since the 1990s is due to size-selective fishing, reduced size at maturation, poor condition of cod, hypoxia, and parasite infestation.

In general, benthic fish stocks (flatfish species that live on the seabed, such as flounder) show a reduction of overall F since 2010, but an increase in the last few years.

Figure 8: Time-series of annual relative fishing mortality (F to FMSY ratio) for benthic, demersal, and pelagic stocks. Table A1 in the Annex details which species belong to each fish category.

Discards

Discarding still occurs in the Baltic, though it is illegal for the major commercial fisheries. For example, for the eastern Baltic cod stock, discards were still estimated at 3238 tonnes in 2017, despite a landing obligation since 2015. Discarding was at similar levels in 2016 and constituted 11% of the total catch in weight.

Impacts on foodwebs and regime shift

Fishing has changed both foodwebs and the community structure in the Baltic Sea. Sudden changes occurred in the foodweb of the central Baltic ecosystem in the late 1980s and early 1990s which, in addition to abiotic changes, can be partly explained by unsustainable fishing pressure.

Impact on spatial distribution and fisheries in the southern Baltic

Sprat and herring are important food items for cod, but at present, the main part of their biomass is distributed north of the distribution area for eastern Baltic cod (Figure 9). The fishery for sprat occurs throughout the range of the stock. ICES has advised that a spatial management plan is developed for fisheries that catch sprat, with the aim to improve feeding conditions for cod.

Impacts on threatened and declining fish species

ICES has advised that all anthropogenic impacts, including recreational and commercial fishing on eels, should be reduced to as close to zero as possible in order to conserve this critically endangered species.

Impacts on seabirds and marine mammals

Drowning in fishing gear is considered to be a significant source of anthropogenic mortality for long-tailed duck, scoters, divers, and some other waterbirds, especially in wintering areas with high densities of waterbirds. Estimates in the early 2000s indicate that between 100 000 and 200 000 waterbirds were being bycaught annually in nets in the Baltic and North seas, mostly in the Baltic. Diving waterbirds are especially vulnerable to being entangled in gillnets and other types of static nets.

Drowning in fishing gear is considered to be the main cause of anthropogenic mortality for harbour porpoise populations in the Baltic Sea, and is also a concern for grey seals.

Hunting

Hunting was the main reason for a drastic decline in grey seal and ringed seal populations in the early 1900s. In the 1970s and 1980s, seals were protected by all countries in the Baltic Sea region. After recovery of the populations, controlled hunting is allowed. The highest permissible annual quota is presently around 2000 grey seals, 230 ringed seals, and 235 harbour seals. White-tailed sea eagle Haliaeetus albicilla and cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo almost disappeared from the Baltic Sea in the early 1900s due to hunting or intentional killing.

Sea ducks have traditionally been hunted, with the most common target species in the Baltic Sea being common eider Somateria mollissima and long-tailed duck Clangula hyemalis. The average annual number of hunted individuals of these two species in recent years has been around 37 000 and 16 000, respectively.